In the heart of Crete's bustling capital, a treasure trove awaits those curious about the island's ancient past. The Heraklion Archaeological Museum is not just one of the largest museums in Greece – it is the premier repository of Minoan civilization artifacts in the world. For anyone even remotely interested in history or art, a visit here is a journey into the Bronze Age culture that flourished on Crete over 3,500 years ago. But the museum's scope goes beyond Minoan times: its 27 galleries chronologically showcase finds from Neolithic Crete to the Roman era, spanning an astonishing 5,500 years of history. Newly renovated and beautifully curated, the Heraklion Museum is immersive – where else can you stand face-to-face with the enigmatic Phaistos Disc, the delicate faience Snake Goddess figurines, or the bull's head drinking vessel that looks as if a real bull was petrified mid-roar? Often considered the best in the world for Minoan art, this museum is the key to understanding the archaeological sites you explore on Crete. Let's step inside and highlight what you shouldn't miss.

'Heraklion Archaeological Museum' - Attribution: D-Stanley

'Heraklion Archaeological Museum' - Attribution: D-StanleyA Showcase of Minoan Splendour

Upon entering, you'll find that the museum's ground floor is largely devoted to Crete's star attraction: the Minoan civilization (c. 3000–1400 BC). The collection is so vast that it occupies roughly 20 rooms and covers everything from Minoan daily life to religion and palace culture. Crete's first high civilisation comes alive through these objects – indeed, the museum prides itself on its unique Minoan collection, rightly considered the most important and complete in the world.

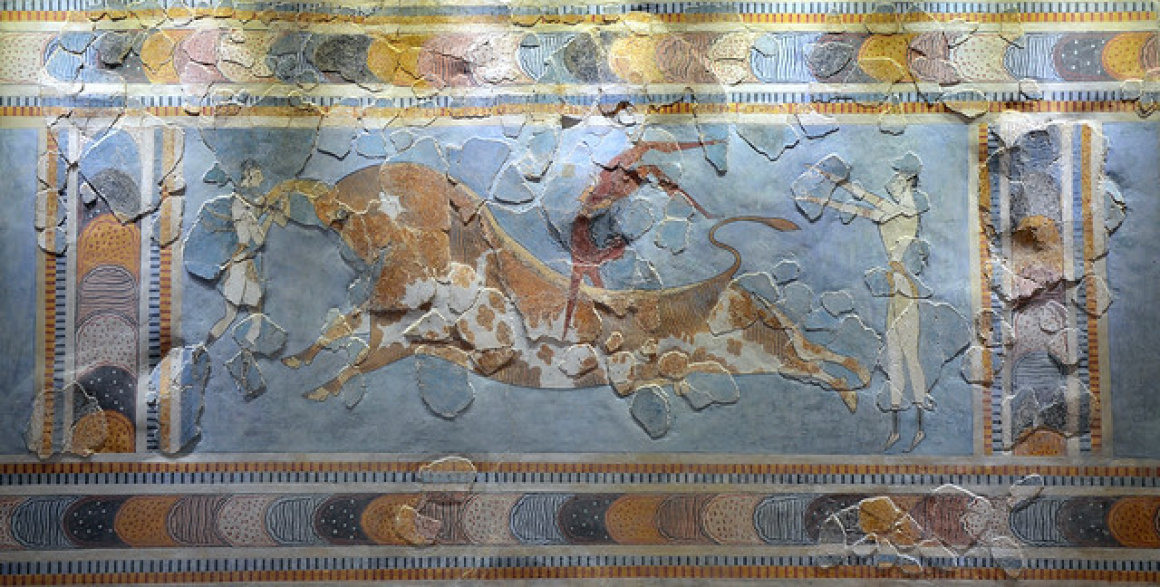

'Minoan fresco depicting a bull leaping scene, found in Knossos, 1600-1400 BC, Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete' - Attribution: Following Hadrian

'Minoan fresco depicting a bull leaping scene, found in Knossos, 1600-1400 BC, Heraklion Archaeological Museum, Crete' - Attribution: Following HadrianStart in the Prehistoric rooms where early farming communities' clay figurines and tools show the genesis of Cretan society. Then, as you progress, the displays blossom into the high Minoan period. Room IV is often a highlight – here you meet the famous Snake Goddess figurines (about 1600 BC). These are small faience statuettes depicting a bare-breasted female deity holding serpents in outstretched arms. There's an inexplicable power to them, with their intense eyes and elaborate costumes; they give a glimpse of Minoan religion, where a mother goddess figure was prominent. Nearby is the mysterious Phaistos Disc, a baked clay disk (maybe 15 cm across) stamped on both sides with a spiral of symbols. Despite numerous attempts, its “text” is undeciphered – one of the great puzzles of archaeology. Seeing it in person, its symbols (little human figures, animals, tools) are remarkably well-preserved. You can almost imagine the ancient hand that pressed those seals into the clay one by one around 1700-1600 BC.

'Snake goddess' - Attribution: sipes23

'Snake goddess' - Attribution: sipes23Moving on, don't miss the beautifully crafted Minoan jewellery and metalwork. The iconic Bee Pendant from Malia is displayed in a case – two golden bees enameled in filigree holding a honeycomb drop. It's astonishingly intricate for something from 1800 BC. Nearby, the Bull's Head Rhyton from Knossos stuns visitors. This libation vessel is carved from black steatite into the shape of a bull's head, with mother-of-pearl snout and gilded horns; ritual liquid would be poured from its mouth. It's so life-like you almost expect it to snort! The bull motif recurs in Minoan art, reflecting the significance of bull-leaping and the myth of the Minotaur.

One room is dedicated to the famous Minoan frescoes. These vivid wall-paintings, painstakingly reconstructed from fragments found at Knossos and other sites, line the walls in glorious colour. The “Bull-Leaping” fresco (Knossos) shows a youth vaulting over a charging bull – the dynamic movement and curved lines capture a sense of action. Next to it, the “Prince of the Lilies” (or “Priest-King”) fresco showcases a figure with a large plumed crown leading, perhaps, a ceremony – though note that modern research suggests this may be a composite made by Arthur Evans and not actually a singular figure in the original. Equally enchanting are the miniature frescoes like the Ladies in Blue (elegantly dressed Minoan women chatting) and the Monkeys and Birds fresco from Akrotiri (Thera) on Santorini, included here to show Aegean connections. Seeing the frescoes up close, one appreciates their delicate details – the distinct profile pose, the rich blue made from Egyptian azurite, the flowing forms of nature. They feel astonishingly modern in aesthetic.

Another must-see artifact is the clay model of a Minoan house from Archanes – a sort of architectural maquette that survived and gives a tangible peek into building styles (complete with tiny windows and doors). And keep an eye out for the small but evocative ivory figurine of an acrobat from Knossos, captured mid-flip – just a few inches tall, it's amazing such a fragile piece survived since 1500 BC.

Throughout these Minoan rooms, you get a sense of a vibrant, nature-centric, sophisticated culture. What's wonderful is how the museum balances the artistry of these objects with context about their functions. Descriptive panels (in Greek and English) explain, for example, how large storage jars (pithoi) were used to hold olive oil or grain in palace magazines, or how clay Linear B tablets (on display) were essentially bureaucratic records – listing goods, likely used by palace scribes around 1450 BC. (Linear B, deciphered in 1950s, turned out to be the earliest form of Greek – another highlight: you can see the famed Linear B tablets, including the one that lists weapons found at Knossos.) These touches connect the stunning art to everyday life and administration, deepening appreciation.

Practical Visit Tips

The museum is centrally located in Heraklion, easy to find on Xanthoudidou Street by the Eleftherias Square. If you come from Knossos site first (which is recommended, to then appreciate the artifacts), note that a combined ticket is available (it's about €20 and covers both the palace and museum). The museum is open daily (longer hours in summer). In peak season, coming right at opening (8am) or late afternoon gives a more peaceful experience, as midday it can be quite full with tour groups fresh from Knossos. The building is modern, air-conditioned (a relief on hot days), and has an interior courtyard where you can take a break.

Photography is allowed (no flash). It's tempting to photograph everything, but don't forget to just look with your eyes; some details a camera can't capture well, like the 3D depth of relief carving.

Facilities: There's a ground floor cafeteria and gift shop. The shop has quality reproductions (like of the Snake Goddess, Phaistos Disc, bee pendant, etc.) and books. A nice souvenir many get is a pendant of the Phaistos Disc or Bee in gold or silver. The café does decent snacks and coffee, but you might instead opt to walk to one of the many eateries nearby in the town center after your visit.

'Female Goddess - Heraklion Archaeological Museum - Crete' - Attribution: Lark Ascending

'Female Goddess - Heraklion Archaeological Museum - Crete' - Attribution: Lark AscendingPlan at least 2 hours to do it justice (passionates could spend half a day easily). The exhibits are logically organised in chronological order, but don't be afraid to skip ahead or target what interests you most if time is short. For example, if Minoan is your focus, concentrate on those rooms, then quickly walk through the later periods.

One delight is that after you've visited other parts of Crete, you can often tie things back to what you saw in the museum. Hiked the Armeni tombs near Rethymno? You likely saw the helmet from Armeni in the museum. Went to Knossos? The disc and many finds are here. Toured a village church? The museum's early Christian section echoes it.

Accessibility: The museum is accessible via elevators, and it's one of the more wheelchair-friendly ones in Greece. It has a cloakroom where you should leave large bags.

Bringing the Past to Life

The Heraklion Archaeological Museum truly brings to life more than 5,500 years of history. By the end of your visit, you'll have a more comprehensive picture of Crete's past: the evolution from the mythic labyrinthine palaces of the Minoans, through the post-palatial period and integration into the Greek world, the influence of Hellenistic kingdoms, and the might and eventual Christian transformation under Rome. For many, the Minoan section leaves the deepest impression – it's hard to shake the feeling of connection when looking into the eyes of a 3,600-year-old figurine or admiring a fresco pigment that still pops with colour millennia later. You come away realising that in some ways these ancient Cretans are familiar – they loved art, sports, nature, and ritual – and in other ways, alluringly mysterious.

To complement your museum visit, consider also seeing the Historical Museum of Crete (also in Heraklion city) which picks up where this museum leaves off – covering Byzantine, Venetian, and modern era Crete. Together, these museums cover an unbroken timeline from Neolithic farmers to 20th-century resistance fighters. Few places can boast such continuity.

In summary, the Heraklion Archaeological Museum is an essential stop on any Cretan itinerary. It's not an exaggeration to say it's one of the top museums in Greece and even Europe for ancient art. As you depart, think of the journey you've taken: from the Neolithic farmer's clay cup to the Roman governor's portrait bust. Crete's history is now a part of your experience, and the images of Minoan dancers, proud goddesses, and playful dolphins will likely stay with you long after you've left Crete's shores.