In May 1941, Crete became the stage for one of World War II's most dramatic battles – the Battle of Crete. This battle was unique in WWII history as the first primarily airborne invasion and one of the few times the local civilian population took up arms en masse against the invader. The events, heroism, and tragedies of those days left a deep imprint on the island's memory. Let's delve into this compelling chapter.

Background

World War II reached Crete after mainland Greece had fallen. It was 1941, Nazi Germany had invaded Greece in April to support its ally Italy (whose forces had been pushed back by the Greeks). British and Commonwealth forces, after fighting in mainland Greece, retreated to Crete along with Greek units, making the island the next line of defence. Crete was strategically vital – it could host airfields to control the eastern Mediterranean and threaten Axis oil routes. Hitler launched Operation Mercury, the code name for the invasion of Crete. The British had a garrison on Crete (called “Creforce”), consisting of roughly 32,000 troops (British, Australian, New Zealander, and Greek soldiers), but many were exhausted and lightly equipped after the mainland campaign. They did, however, have one intelligence edge: the Allies had partially cracked the German Enigma codes, so they had advance warning that Crete would be attacked from the air. Despite this, the Allied defence had weaknesses – limited heavy weapons, almost no aircraft or tanks on Crete, and an overall lack of coordination and communication equipment.

The Invasion (20 May 1941)

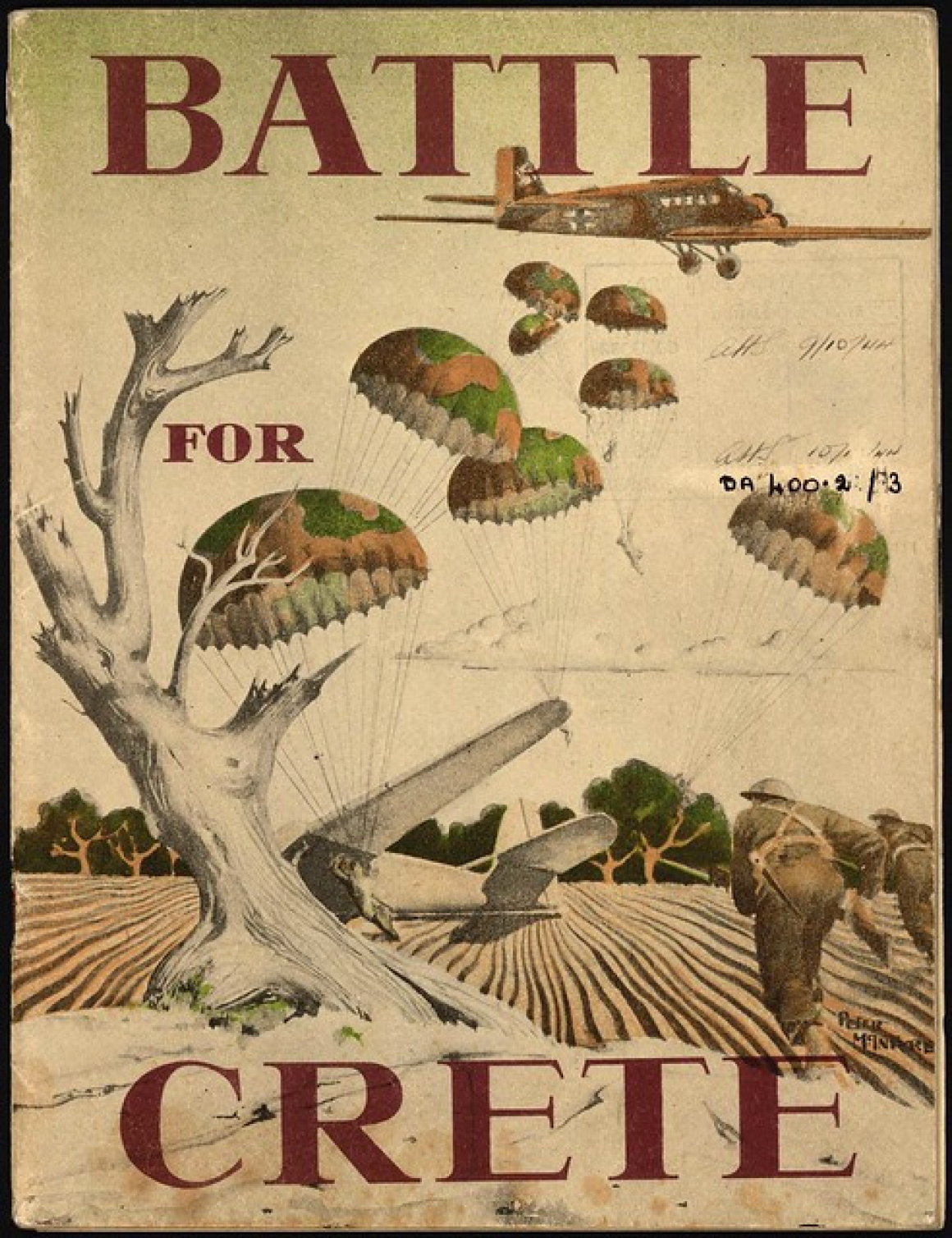

On the morning of 20 May 1941, the sky over Crete roared with aircraft engines. The Germans launched a massive airborne assault, dropping over 8,000 elite Fallschirmjäger (paratroopers) at key points: Maleme (west of Chania), Rethymno, and Heraklion – all areas with airfields. Thousands of troops descended by parachute or arrived in gliders. It was the first large-scale airborne invasion in military history. The initial German drops met with fierce resistance. At Maleme, New Zealand troops and Cretan militia inflicted very heavy casualties on the parachutists. Many planes were shot down or crash-landed. In fact, German losses on that first day were so high that the local German commander almost considered the mission a failure.

Crucially, the German forces at Maleme managed to secure the vital airfield by the second day, partly because of miscommunication among the Allied defence that led to a withdrawal from a key hill overlooking the airstrip. Once Maleme airfield was in German hands, the invaders were able to fly in reinforcements (troops and supplies) by plane. This turned the tide. The Germans poured in more soldiers of the 5th Mountain Division, tipping the balance in the western sector. Over the next days, heavy fighting raged across the island's north. The towns of Chania, Rethymno, and Heraklion were all bombed and attacked. The Allies, though outnumbered and outgunned from the air, fought bravely, as did the local Cretan civilians – who in many cases armed themselves with old rifles, knives, or even farming tools to attack German paratroopers. This civilian resistance shocked the Germans, they had not expected the local population to join the fight. It led to brutal reprisals (in later days, German forces executed villagers suspected of attacking their troops). Still, the Cretans' courage was notable – Cretan civilians fought alongside Allied soldiers, an uncommon phenomenon in WWII.

By 27 May, the Allied commanders realised the situation was untenable. Maleme and the western sector were lost, and German troops were advancing toward Chania and Souda Bay. An evacuation was ordered. In a Dunkirk-like scenario, Allied troops were to be evacuated by sea from the south coast (the northern ports were too exposed to German control). About 16,000 Allied troops were evacuated from Sfakia on the south coast over several nights by the Royal Navy, escaping to Egypt. However, many could not be rescued in time.

Significance and Legacy

The Battle of Crete was pivotal in several ways. It delayed German plans slightly (some argue it shifted the timetable of the invasion of the Soviet Union, though by only a few weeks). It taught the Germans that the element of surprise is vital for airborne assaults – after Crete, Hitler never again approved a major airborne operation, considering it not worth the cost. For the Allies and occupied peoples, Crete became a symbol of defiance: the islanders' resistance showed that even without heavy arms, a population could complicate an invasion. Winston Churchill praised the bravery of the Cretans, and stories of villagers attacking paratroopers with kitchen knives or old muskets became legend.

However, Crete paid a heavy price during the occupation (1941–1945). The Germans stationed forces on Crete and the island remained under Axis control until the war neared its end. The Cretan Resistance movement was one of the most active in Greece. Cretan partisans, aided by a few British SOE agents who stayed behind (like the famous Patrick Leigh Fermor), waged guerrilla warfare from the mountains. They sabotaged German installations, gathered intelligence, and even carried out one of the war's boldest resistance operations: the kidnapping of General Kreipe, the German commander, in 1944 (spiriting him off the island to Egypt). The local population often sheltered Allied soldiers who evaded capture – many lived in mountain villages or caves, protected by locals at great personal risk. German reprisals were brutal: entire villages were razed and civilians executed in retribution for resistance activities. For instance, the villages of Kandanos, Anogia, and Viannos saw mass murders of inhabitants by occupying forces. This tragic aspect of the Battle of Crete's aftermath is commemorated by monuments and memorials across the island.

The legacy of the battle is evident today. War cemeteries on Crete honour those who fell. In Souda Bay near Chania, the Commonwealth War Cemetery is a serene field of white headstones facing the sea, containing the graves of Allied soldiers (British, Australian, New Zealander, etc.) who died in the battle. Similarly, on a hill overlooking Maleme is the German War Cemetery at Maleme, where the remains of over 4,000 German troops are kept, a somber reminder of the cost of war. Every May, events are held to commemorate the Battle of Crete. Veterans (in earlier decades) and now their descendants, as well as locals, gather for memorial services. Ceremonies at Souda Bay Cemetery include wreath-laying and the playing of the Last Post, and Cretan officials and Allied representatives pay respects. The locals also host events showing traditional gratitude, for example, in Galatas and around Maleme, remembering how villagers and foreign soldiers fought side by side.

For those interested in history, there are a couple of museums worth visiting: The “Museum of the Battle of Crete and National Resistance” in Heraklion is dedicated to this period, displaying photographs, weapons, and personal stories of Cretan fighters and Allied soldiers. In Chania, the War Museum (housed in an old Venetian church building) also covers the battle and occupation. Additionally, the Historical Museum of Crete in Heraklion has a section on WWII. At Maleme, near the airfield, you can still see the ground where this decisive engagement played out, a small visitors' centre and memorial there provide context.

The Battle of Crete stands as a testament to Crete's strategic importance and the indomitable spirit of its people. When you stand at the crest of Hill 107 in Maleme (site of the German cemetery now) and look over the peaceful olive groves and the sparkling Sea, it's hard to imagine the fierce combat that took place there. But the peace and freedom Crete enjoys today came at the cost of those sacrifices. The island's motto “Freedom or Death” (Eleftheria i Thanatos) – shared with the rest of Greece – was truly lived out during those critical days of 1941.

'Battle for Crete' - Attribution:

'Battle for Crete' - Attribution: